Chronicles Guanajuato, Aguascalientes, Nayarit, Colima

Here I am going to recount some of the conversations and interventions from the meetings in Aguascalientes, Guanajuato, Nayarit, and Colima, chronicle style. See other entries, above and below, for analysis.

Here I am going to recount some of the conversations and interventions from the meetings in Aguascalientes, Guanajuato, Nayarit, and Colima, chronicle style. See other entries, above and below, for analysis. 3.16.06. Aguascalientes. A self-identified housewife in Cañada Onda, Aguascalientes, who gives an elegant speech thanking Marcos’s mother for creating him and letting him think for himself, speaks of her idea of autonomous thinking and raising children: I have always tried to make my own judgment.

Those of us that have children, sons and daughters, students, nieces/nephews, this is the way to change this country: “we have to commit ourselves to not making obedient people, people that process orders. We can’t have a country of “obedients,” not on any level.” I remember a woman in Oaxaca, in the tiny town of Union Hidalgo, who said, condemning both the machista and submissive subjectivities created in capitalism, “better to die a virgin then give birth to fools.” The housewife in Aguascalientes says at the end of her intervention, “Today I escaped my house and my work, but don’t forget about all those women who couldn’t come. Our struggle, like this struggle (the Sixth, the Other), is everyday, everyday we come out different.”

Those of us that have children, sons and daughters, students, nieces/nephews, this is the way to change this country: “we have to commit ourselves to not making obedient people, people that process orders. We can’t have a country of “obedients,” not on any level.” I remember a woman in Oaxaca, in the tiny town of Union Hidalgo, who said, condemning both the machista and submissive subjectivities created in capitalism, “better to die a virgin then give birth to fools.” The housewife in Aguascalientes says at the end of her intervention, “Today I escaped my house and my work, but don’t forget about all those women who couldn’t come. Our struggle, like this struggle (the Sixth, the Other), is everyday, everyday we come out different.” Aguascalientes has a broad spectrum of participants—housewives, students, religious clergy, young people, gay community, students, communist party members, etc. There is a fair representation of anarcho-punks present, pierced and tattooed, dressed mostly in black and hair gelled to defy gravity and conformity. But these are not just aesthetics. “The first thing that is exploited is the body,” they claim in front of their new compañeros housewives, students, priests, EZLN, “our discrimination is not just rejection of our style, it is a hate of difference, hate of the other.” An older man describes an autonomous project that a group of elderly neighbors have created, a house that they share that runs on windpower and solar power. Students from the university in the capital of Aguascalientes make clear that what they fight for can’t be granted them from powers above, but requires another politics altogether: “we don’t just want free and public education, because the education we’re receiving is capitalist training.

Aguascalientes has a broad spectrum of participants—housewives, students, religious clergy, young people, gay community, students, communist party members, etc. There is a fair representation of anarcho-punks present, pierced and tattooed, dressed mostly in black and hair gelled to defy gravity and conformity. But these are not just aesthetics. “The first thing that is exploited is the body,” they claim in front of their new compañeros housewives, students, priests, EZLN, “our discrimination is not just rejection of our style, it is a hate of difference, hate of the other.” An older man describes an autonomous project that a group of elderly neighbors have created, a house that they share that runs on windpower and solar power. Students from the university in the capital of Aguascalientes make clear that what they fight for can’t be granted them from powers above, but requires another politics altogether: “we don’t just want free and public education, because the education we’re receiving is capitalist training.  We don’t want free capitalist training!” A local priest stands up with a plea for a different church: the god of life, he says, is from below, and this god walks to the left, with us, with the soul of this movement. The official church may have its position in the state electoral system, but there is a faith from below too. Another church is possible! Someone from the local LGBT insists to the other participants, our struggle is not far from yours, we are part of you, we also have desire to struggle, and “we don’t want closets any more than we want prisons or graves.” And another participant, “Democracy should be a form of life, not a method to process politicians.”

We don’t want free capitalist training!” A local priest stands up with a plea for a different church: the god of life, he says, is from below, and this god walks to the left, with us, with the soul of this movement. The official church may have its position in the state electoral system, but there is a faith from below too. Another church is possible! Someone from the local LGBT insists to the other participants, our struggle is not far from yours, we are part of you, we also have desire to struggle, and “we don’t want closets any more than we want prisons or graves.” And another participant, “Democracy should be a form of life, not a method to process politicians.” 3.12.06. Guanajuato. In Salamanca, the most contaminated city in all of Mexico, the people talk about the high indices of leukemia and other cancers, skin diseases, asthma, respiratory diseases. The factory Tekim, a US company, employs some 500-700 workers, is the source of the pollution; but it is not just the workers who are sick. The water reserves, the air, and the soil have been contaminated by the factory emissions. The people say that the smell can sometimes make one vomit, that the factory has to release emissions all night because it is too much to bear during the day. A few years ago there was an explosion in the factory, and the people say that when the yellow mushroom cloud arose above the factory the food in their houses went bad and clothes disintegrated. There are only two more factories like this in the entire world—one in China and one in India. Today, when the Other Campaign travels through this city, the yellow smoke and putrid smell have strangely absent—work suspended for the day.

3.12.06. Guanajuato. In Salamanca, the most contaminated city in all of Mexico, the people talk about the high indices of leukemia and other cancers, skin diseases, asthma, respiratory diseases. The factory Tekim, a US company, employs some 500-700 workers, is the source of the pollution; but it is not just the workers who are sick. The water reserves, the air, and the soil have been contaminated by the factory emissions. The people say that the smell can sometimes make one vomit, that the factory has to release emissions all night because it is too much to bear during the day. A few years ago there was an explosion in the factory, and the people say that when the yellow mushroom cloud arose above the factory the food in their houses went bad and clothes disintegrated. There are only two more factories like this in the entire world—one in China and one in India. Today, when the Other Campaign travels through this city, the yellow smoke and putrid smell have strangely absent—work suspended for the day. The same people who give us daily “massive toxic cocktail,” one man states at the meeting of the Other Campaign, are those who hide the information about our health. “None of our women our healthy,” a middle-aged woman, a cancer-survivor, claims, we all have cancer, leukemia, other diseases, and now our kids are born with these diseases. The Plan Puebla Panama will create many more Salamanca’s another participant warns, and the crowd chants, “Nunca mas otra Salamanca!” “Never again another Salamanca,” not in the republic of Mexico, one man adds, and not on the planet.

The same people who give us daily “massive toxic cocktail,” one man states at the meeting of the Other Campaign, are those who hide the information about our health. “None of our women our healthy,” a middle-aged woman, a cancer-survivor, claims, we all have cancer, leukemia, other diseases, and now our kids are born with these diseases. The Plan Puebla Panama will create many more Salamanca’s another participant warns, and the crowd chants, “Nunca mas otra Salamanca!” “Never again another Salamanca,” not in the republic of Mexico, one man adds, and not on the planet.3.13.06. Guanajuato. In the capital of Guanajuato the substance of the meeting is dominated by the local miner’s struggle and by the interventions by young people

denouncing their repression. The young people talk of harsh police repression against not just their politics, but their presence in the street, their style, their very existence. One young man with a broken arm and his face covered with handkerchief begins to denounce the repression from behind the hankerchief, and then rips it off as he is speaking, “it does no good to hide myself,” he says motioning to his cast, “they obviously know who I am already.” There is an intensely hopeful moment, characteristic of the most acute realizations of the Other Campaign, when the EZLN directs its words of the young people and the miners, saying: In front of all the orejas (spies) here today, the representatives from the Yunque (semi-secret group of PAN politicians and corporate elite that basically runs states at least where the PAN is in power, more on this later), and the police that are listening, we’re here to say, you are not alone, now among your compañeros in struggle is the Zapatista Army for National Liberation. The miners and the young people cheer wildly, joyfully, militantly.

denouncing their repression. The young people talk of harsh police repression against not just their politics, but their presence in the street, their style, their very existence. One young man with a broken arm and his face covered with handkerchief begins to denounce the repression from behind the hankerchief, and then rips it off as he is speaking, “it does no good to hide myself,” he says motioning to his cast, “they obviously know who I am already.” There is an intensely hopeful moment, characteristic of the most acute realizations of the Other Campaign, when the EZLN directs its words of the young people and the miners, saying: In front of all the orejas (spies) here today, the representatives from the Yunque (semi-secret group of PAN politicians and corporate elite that basically runs states at least where the PAN is in power, more on this later), and the police that are listening, we’re here to say, you are not alone, now among your compañeros in struggle is the Zapatista Army for National Liberation. The miners and the young people cheer wildly, joyfully, militantly. 3.26.06. Nayarit. In Tuxpan, Nayarit, Immigration is once again a principal theme, but for the first time in a long time, someone refers to “Imperio,” or Empire, in relation to the movement of international capital and labor. After one man asks, how can they turn us into consumers of our own products, employees on our own land? Another points to the student protests in France, the immigrant protests in Los Angeles, their own immigration flow in Tuxpan: capitalism is the same in Tuxpan, France, Brazil, the United States, he says, this is the same struggle, it is the same empire. If Fox could, he’d sell Marta another says, jokingly but bitterly, referring to Vicente Fox, the Mexican president, and his wife, Marta Sahagun.

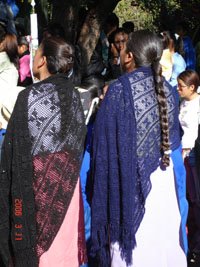

3/29/06. Colima. On our way to Yerba Buena, Colima, an indigenous Nahuatl community situated halfway up the side of a volcanic mountain, the volcano erupts in front of the sunset, treating us to pink and yellow and purple tinged gases rising from the mountain. This is the volcano that powerful caciques and local government are using as an excuse to displace the indigenous communities living there. The “danger” however doesn’t seem to apply to the luxury resort built on the same lava-laden land, one of the most exclusive resorts in the world, costing close to 3,000 US dollars per night. Bad enough would be if these people were turned to the servants of the international rich on their own land, but there is not even this opportunity for work; the hotels, this one with owners in Hong-Kong, come with labor power included, they will have nothing to do with the poor inhabitants of this land. In the meeting in Yerba Buena, where the soil is black with ash, indigenous participants relate: this culture that we have is much older than this flag (the Mexican flag) that we have just saluted. As pre-american people, our values have always been autonomy, autarchy, and self-sufficiency. But we are not purists or traditionalists, there has to be a synthesis of western culture and indigenous culture. And another adds, “This struggle to self-determine cannot work locally, it will only work at a national level, or perhaps only at the global level.”

3/29/06. Colima. On our way to Yerba Buena, Colima, an indigenous Nahuatl community situated halfway up the side of a volcanic mountain, the volcano erupts in front of the sunset, treating us to pink and yellow and purple tinged gases rising from the mountain. This is the volcano that powerful caciques and local government are using as an excuse to displace the indigenous communities living there. The “danger” however doesn’t seem to apply to the luxury resort built on the same lava-laden land, one of the most exclusive resorts in the world, costing close to 3,000 US dollars per night. Bad enough would be if these people were turned to the servants of the international rich on their own land, but there is not even this opportunity for work; the hotels, this one with owners in Hong-Kong, come with labor power included, they will have nothing to do with the poor inhabitants of this land. In the meeting in Yerba Buena, where the soil is black with ash, indigenous participants relate: this culture that we have is much older than this flag (the Mexican flag) that we have just saluted. As pre-american people, our values have always been autonomy, autarchy, and self-sufficiency. But we are not purists or traditionalists, there has to be a synthesis of western culture and indigenous culture. And another adds, “This struggle to self-determine cannot work locally, it will only work at a national level, or perhaps only at the global level.”

Other participants denounce the image Colima is given as a pretty, peaceful vacation spot for foreigners. Peace? One man asks, here we have one of the highest rates of cancer in the nation, also for sexual violence; hate crimes abound, and nobody is going to solve this for us, not even the Sup (Marcos). We have to solve this ourselves. In a region ruled by caciques and characterized by the master-peon relationship, our best master, another adds, is our own organization.

In all these places, in response to the complaints and denunciations against the “bad government,” the EZLN clarifies its analysis: The government is not neglecting its duties, it is doing its job and it is doing it well.

The chronic sicknesses and terminal illnesses characterizing so many of these places as a result of industrial contamination, the forced displacements and environmental destruction created by the mega-projects of an international capitalist class, and the promises, betrayals, and hand-outs that keep people obedient and subservient to a political class that has long lacked, if it ever had, any representational integrity are not instances of neglect, but of capitalist valorization.

The chronic sicknesses and terminal illnesses characterizing so many of these places as a result of industrial contamination, the forced displacements and environmental destruction created by the mega-projects of an international capitalist class, and the promises, betrayals, and hand-outs that keep people obedient and subservient to a political class that has long lacked, if it ever had, any representational integrity are not instances of neglect, but of capitalist valorization.The EZLN in Guanajuato: “This is the same system that considers the indigenous as ignorant, the young people as hell-raisers, the women as sluts, the kids as idiots, the old people as disposable, workers as leaches, students as something to tolerate until they become functional workforce, teachers as mere reproducers of the same thing that already exists above.” Capitalism does not impose through free contracts, they remind us, it is born in blood and mud.