January 18

Three important trajectories emerge in the writings, meetings, and words of the Sexta, both in the preliminary meetings in the fall in the Selva and in these first weeks of January circulating through Chiapas (this appears again below because I placed it wrong and I'm having editing

difficulties in changing it)

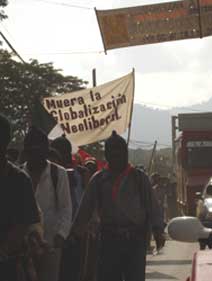

The first is that the Sexta, the movement that has been launched with the 6th Declaration of the Lacondon Jungle, is anti-capitalist. This is significant because the discourse around zapatismo has often been specifically anti-neoliberal, certainly critical of current global economic policy, but only sporadically vocally anti-capitalist, though the practice has always been that. Now, however, all the language of the Sexta is explicitly, repeatedly, and with much emphasis anti-capitalist. In each city and village the caravan travels, in fact, Delegado O takes the local economy as an example—whether that is fisheries, farms, factories, the tourism industry—and describes the current conditions of inequality and exploitation in terms of primitive accumulation—the theft, plundering, expropriation, and legalized robbery that enables the capitalist class structure. That accumulation process continues, the people in nearly every part of Chiapas have pointed out: we work hard all day everyday and in the end all we have is the same shit or worse. It’s the same everywhere, Delegado O repeats, it’s the same in the jungle, in Palenque, in Tonala, in Huixtla, here in this tiny coastal fishing village of Joaquin Amado, it’s the same in Sinaloa, Tijuana, Mexico City, and it’s the same in “el otro lado,” or the “other side” of the border, the United States. In Huixtla, the damage from Hurricane Stan was fierce and the aid and repairs never arrived, despite all the TV spots, sponsored by political parties, showing a ceremonial photo-opp delivery of goods to affected communities. A student from the UNAM gets up to speak in Huixtla and describes the clean-up activities the students did for the damnificados, or victims of the hurricane. But we have not done enough, she continues, because we are all damnificados, not of Stan but of capitalism and the unemployment, poverty, and misery it brings to all of us. We are fighting for a free and public university system, she says, but what good does a free education do if young people don’t have the resources to feed themselves day to day?

The interesting thing here is that, through the discourse of the Sexta, there is growing, widespread critique of the economy throughout Mexico not just in terms of inflation, corruption, and foreign expropriation, but specifically of capitalism as a system. Capitalism becomes a recognizable phenomenon, instead of a system hiding behind it’s symptoms of “consumer confidence,” “market fluctuations,” or inevitable economic cycles. Imagine a common critique, or at least recognition, of capitalism in the U.S.!

Second, and closely related, is the clear rejection of electoral politics and state solutions, rather than just a critique of corrupt politicians or the party in power. Change will not come from above, Delegado O repeats in nearly every meeting, and inevitably the people murmur and nod when he clarifies: what is screwing us over here is a system, sometimes its is tri-colored, sometimes blue, sometimes black and yellow (referring to the respective colors of the PRI, PAN, and PRD, the three primary political parties in Mexico), but who cares what color they put on if we continue seeing the same gray? If everyday is a gamble whether we will wake up the next? Or if we will be in jail by tonight? Choosing a candidate and a party is just choosing which one will beat us up, refuse to pay us for our work, put us in jail, kill or disappear us. But it is not just that these parties are corrupt, he pushes further, it is a system, not just political and economic but also representational, that we do not want. How long are we going to sit here waiting for someone to do for us what we have to do ourselves? How long will we waste our time voting to delegate someone above to do what can only be done from below?

Which brings us to the third trajectory: subjectivity. There is no room in the Sexta for anyone to stand on the outside and offer support, service, solidarity with the movement. We ARE the movement. This is a big adjustment for “civil society”: for twelve years they had to learn to listen to the Zapatistas, even (and especially) when they were silent. But now they/we are being asked to speak, and to speak of their own struggles. The only way to join the Sexta is to join as a compañeo in struggle. The question the EZ poses in the Sexta is no longer do you understand our struggle and do you support it, but, what is your struggle?

January 16

In Quintana Roo, Subdelegado O talks about the decision Comandanta Ramona had to make. She had to decide whether to get married and have a home and a family, or to do political work, because, as a woman, this was a choice she had to make. Ramona and Susana, another insurgenta began the organizational work with women, going community to community, kitchen to kitchen, talking to the women of the communities, and all this before there were roads or t

ransport. And after 10 years of this organizing work, they wrote the Zapatista Revolutionary Law for Women which the delegado describes, “where they claimed important rights that may sound funny to you, but they were radical claims, like women could be drivers! They could move about without depending on a man, probably drunk anyway, to drive them.” Susana is coming back, he informs the people in Quintana Roo, this fall when the Zapatistas comandantes leave the jungle to spread throughout the country and stay with the people for a longer time to learn about their lives and struggles, Susana is coming here. So take your time, think about it carefully, he urges as he has in each city and town so far, and then decide if you want to join us. We won’t come solve your problems, we will only bring more, news of the problems everywhere else. But we will come and we will stay and we will all work together.

This is one of the fascinating turns of the Sexta: for 12 years national and international “civil society” have accompanied the Zapatista communities in their struggles, in their defense and their initiatives and their construction of autonomy. Now, as part of the Sexta, and as of September 2006, the Zapatistas are coming out of the mountains and the jungle to accompany communities in the rest of the country in their struggles: “So this is what we are going to do, and we’re not asking you to do a task for us, but rather to receive us, when we return, so that, alongside you, we will go to Chichen Itzá to be with the artisan companeros there while they are making and selling their merchandise, we will go with the companeros of Oxcun, we will be with the women in Yucatan that are meeting to discuss their problems, with the children when they go to school, with the housewives where they are discussing problems of the household or the neighborhood, and this is how we will learn from you, because we are going to struggle all of us together and begin to unite our struggle to others.” Quintana Roo, January 16.

January 20, 2006

January 20, 2006