Stakes of the Sexta

“What we’re doing here, comrades, is without precedent. Not even the models of solidarity with Zapatismo will work here, because this isn’t about solidarity with the indigenous communities. Neither do the existing social and political struggles,  respectable in their own right, serve as a referent for this, because what we are proposing is take a route where there is not yet a path. What’s more, nobody even thought that it was possible to walk where we want to go….” (Marcos, Veracruz, 1/31/06).

respectable in their own right, serve as a referent for this, because what we are proposing is take a route where there is not yet a path. What’s more, nobody even thought that it was possible to walk where we want to go….” (Marcos, Veracruz, 1/31/06).

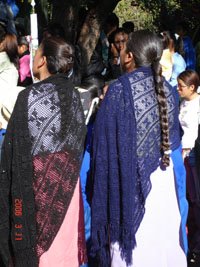

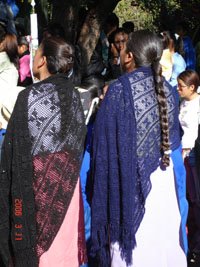

[all the pictures here are either murals in the people listening in the meetings of the Other Campaign, with the exception of two pictures, first and last, of murals in the chiapas caracoles. I have to figure out a way to put captions on them, but for now...].

When the red alert was announced in June of 2005, civil society mobilized in defensive mode, preparing to guard, protect, defend, maintain the security and safety of the EZLN and the Zapatista communities. They prepared to stabilize the situation, to maintain the equilibrium of forces, to help keep things the same.

But the Zapatistas didn’t want stability. They wanted change. They did not want the world to mobilize in their defense, to hold onto what they had, they wanted the world to mobilize in their own struggles, alongside them; for the EZLN this meant to risk everything for something more. This is one of the most beautiful things about Zapatismo. It refuses to be still, to become a rule or a doctrine or a dogma, a subject to identify or an identity to make subject. They refuse to let power accumulate, or find too sure of a rhythm in its path. They keep changing the path, walking a new direction, trying a new talk, teaching us a new word, a new concept of struggle, of the global, of the common.

world to mobilize in their defense, to hold onto what they had, they wanted the world to mobilize in their own struggles, alongside them; for the EZLN this meant to risk everything for something more. This is one of the most beautiful things about Zapatismo. It refuses to be still, to become a rule or a doctrine or a dogma, a subject to identify or an identity to make subject. They refuse to let power accumulate, or find too sure of a rhythm in its path. They keep changing the path, walking a new direction, trying a new talk, teaching us a new word, a new concept of struggle, of the global, of the common.

What the Zapatistas proposed in the Sixth Declaration depends on (at least) four points: our struggle wants to be bigger; what we want can’t be won alone; you can’t help us by lending your support, you must fight with us but you must fight your own struggle; and, the mode and form of this struggle doesn’t yet exist, it must be created.

What comes into question here is “civil society,” the name the EZLN has always used to refer the national and international public, sympathetic with the Zapatista struggle but unarmed and unwilling to take up arms. It was this civil society that took to the streets after the 1994 uprising, demanding the fighting stop so that the EZLN would not be wiped out by the much more militarily powerful Mexican army. In the 1996 dialogues of San Andres Larrainzar, again, the EZLN has recalled, we agreed to meet and negotiate with the government, at the request of civil society. But more importantly than meeting the government, we met you, national and international civil society. The San Andres Accords, in fact, the EZ states, were made among many people, they couldn’t have been made alone, just between us and the government.What Zapatismo became, from the moment when the EZLN listened to the word of the world and called a ceasefire just two weeks after the January 1994 uprising, was a global production.

Over the last decade of struggle, Subcomandante Marcos has said on behalf of the EZLN and the CCRI (Revolutionary Indigenous Clandestine Committee, the body that directs the EZLN on behalf of the base communities), several times and to the deaf ear of many, “autonomy is not just for the indigenous.” This is an important point in light of all the eyebrows raised and foreheads wrinkled with regard to the the EZLN’s harsh criticism of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (supposedly leftist PRD candidate for the presidency). It could have been a strategic move, the wrinkled foreheads have fretted, a strategic alliance or lending of support in order to open more space for the struggle. There are clear and obvious reasons for the EZLN criticism—rejection of the electoral system of representation in general, and the insistence that they couldn’t support a party that had treated them as the PRD had and maintain even a minimum of dignity. But the Sixth makes clear another reason. It may be true that AMLO would have granted the indigenous communities of Chiapas certain rights, certain “autonomy” (though not likely the autonomy they demanded, as this would contradict neoliberal reforms that the PRD supports). But those rights would stay in Chiapas, contained in “indigenous territory.” Perhaps adequate support and protection would be legislated out from the centers of power into these small, “autonomous” communities that, while inspirational, would maintain their distance and marginality from the world, whether that be an oppressive, privileged, or merely isolated margin. But the Zapatistas will not be that margin, that contained and controlled space, that particular.

several times and to the deaf ear of many, “autonomy is not just for the indigenous.” This is an important point in light of all the eyebrows raised and foreheads wrinkled with regard to the the EZLN’s harsh criticism of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (supposedly leftist PRD candidate for the presidency). It could have been a strategic move, the wrinkled foreheads have fretted, a strategic alliance or lending of support in order to open more space for the struggle. There are clear and obvious reasons for the EZLN criticism—rejection of the electoral system of representation in general, and the insistence that they couldn’t support a party that had treated them as the PRD had and maintain even a minimum of dignity. But the Sixth makes clear another reason. It may be true that AMLO would have granted the indigenous communities of Chiapas certain rights, certain “autonomy” (though not likely the autonomy they demanded, as this would contradict neoliberal reforms that the PRD supports). But those rights would stay in Chiapas, contained in “indigenous territory.” Perhaps adequate support and protection would be legislated out from the centers of power into these small, “autonomous” communities that, while inspirational, would maintain their distance and marginality from the world, whether that be an oppressive, privileged, or merely isolated margin. But the Zapatistas will not be that margin, that contained and controlled space, that particular.

In the 1996 Dialogues of San Andres, in the 1996 Intergalactic Encounter, in the 1997 March of the 1,111, in the 1999 National Referendum (the Consulta) in the 2001 March of the Color of the Earth, in the Cathedral Plaza in San Cristobal on January 1, 2003, at the biggest and most militant mobilization of Zapatistas base communities ever when Comandante Tacho hinted that something else was coming, “falta lo que falta….”: in all these moments, the EZ heard the echo, that “the struggle wanted to be bigger.” In an EZLN communiqué to national and international civil society June 21, 2005, shortly before the Sixth Declaration came out, “…imagine what we felt when we saw and heard of the injustices and the rage of the peasants, workers, students, teachers, employees, homosexuals, young people, women, elderly, children. Imagine what we felt in our heart. We touched a heart, a rage, and indignation that we recognized because it was and is ours. But in this moment we touched it in the other. And we understood that the “we” that animated “us” wanted to be bigger, more collective….”

“…imagine what we felt when we saw and heard of the injustices and the rage of the peasants, workers, students, teachers, employees, homosexuals, young people, women, elderly, children. Imagine what we felt in our heart. We touched a heart, a rage, and indignation that we recognized because it was and is ours. But in this moment we touched it in the other. And we understood that the “we” that animated “us” wanted to be bigger, more collective….”

In the Sixth Declaration, the EZLN said it louder still: this struggle is not just for the indigenous, “You’ll remember, six months ago we starting talking about ‘what’s missing’ the communiqué continues, “…well, the time has arrived to decide if we’re going to go and find what is missing. No, not find, build. Yes, build something else.”

Here in the Other Campaign, Marcos says it again, “Our struggle is not indigenist, it’s universal” (Tzinacapan, Puebla 2/13/06),

With the Sixth Declaration of the Lacondon Jungle the EZLN broke through not only the military and security issues that kept them in the mountains and jungle of the Mexican Southeast, but through the political thought of a national and international “civil society.” While many struggles across the globe have understood Zapatismo as something infinitely innovative and transformable, many others could only understand Zapatistmo as something located in Chiapas, among the indigenous, where the political role of “outsiders,” national or international, was to donate time, send money, and write denunciations and press releases condemning army and government abuses. This work was important, it allowed the autonomous municipalities to greatly expand their autonomour structures and improve their quality of life in Zapatista communities, but this was not the full capacity or scope of Zapatismo.

In the heavy, silent days after the Red Alert in June 2005, many local Chiapan and international NGOs and Zapatista solidarity groups around the world whispered about a possible military offensive, possible paramilitary prowlings, black market AK-47s and armed hummers, the incredible asymmetry of forces, The guardians of human rights—other people's human rights—bustled around, checking the old positions, reviving the old conversations, adrenaline high with the possibility of armed warfare, the discourse charged with the moral highground of righteous, humble, poor indigenous communities. Even after the EZLN clarifiee that it was neither predicting nor planning a military offensive, that it had no intent to engage militarily, that the Zapatistas would not be returning to war, the hypotheses rebounded back to troop movements, paramilitary rustlings, drug conspiracies and government set-ups. The theories of what could have spurred this reaction—the red alert and the EZLN reorganization—abounded. Except, perhaps, some hinted, this is not a reaction. Perhaps it is unprovoked, formed not out of opposition or in reaction, but in a generative movement toward something else, not something resisted but something desired.

In the communiqués following the Sixth Declaration, the EZ states clearly to civil society, here you have a choice, you can participate directly, or you can distance yourself from what we do next. You can remain in the aura of that political moment, or you can do politics, which always refers to the present. You can stick to supporting the indigenous fight, thank you sincerely for your help, or you can join us and fight for yourselves.

here you have a choice, you can participate directly, or you can distance yourself from what we do next. You can remain in the aura of that political moment, or you can do politics, which always refers to the present. You can stick to supporting the indigenous fight, thank you sincerely for your help, or you can join us and fight for yourselves.

The Zapatistas have always refused to be what any one wants or expects them to be, to be the object of anyone else’s struggle, to be anyone’s excuse not to politicize their own lives and homes. Zapatismo refuses to be anyone’s vanguard, anyone’s god; it refuses the pedestal so often provided it, the stasis of pyramids, the immobility of being on the top of a ladder so that the only direction to move is down, toppling over. It demands more movement, more freedom, the continuing flow of desire and decision that doesn't stagnate, rest on an object, pool in a position of power, concentrate in an ego. It insists on being a struggle and a strategy, a movement, literally, that generates, multiplies, mutates, expands, and networks, always in the rhythm of what is collective. It is struggle in the most profound sense—the desire to transform and be transformed, to create something different instead of hold onto what is the same.

This is the test for global “civil society,” a test not of their support, but of their desire: Do you want to be free? Can you self-determine? Can you create a common, direct a collective desire, produce something together, live more intensely? Can you exercise power or can you only ask for it? Can you produce power or can you only resist it? Can you create or can you only react? Can you be autonomous, anonymous, anomalous, or can you only be affinity, aid, accompaniment? Do you believe in autonomy or do you believe in exceptionalism? Do you believe that, behind the masks, we are you, or do you believe that, behind your masks, there is nothing?

respectable in their own right, serve as a referent for this, because what we are proposing is take a route where there is not yet a path. What’s more, nobody even thought that it was possible to walk where we want to go….” (Marcos, Veracruz, 1/31/06).

respectable in their own right, serve as a referent for this, because what we are proposing is take a route where there is not yet a path. What’s more, nobody even thought that it was possible to walk where we want to go….” (Marcos, Veracruz, 1/31/06).[all the pictures here are either murals in the people listening in the meetings of the Other Campaign, with the exception of two pictures, first and last, of murals in the chiapas caracoles. I have to figure out a way to put captions on them, but for now...].

When the red alert was announced in June of 2005, civil society mobilized in defensive mode, preparing to guard, protect, defend, maintain the security and safety of the EZLN and the Zapatista communities. They prepared to stabilize the situation, to maintain the equilibrium of forces, to help keep things the same.

But the Zapatistas didn’t want stability. They wanted change. They did not want the

world to mobilize in their defense, to hold onto what they had, they wanted the world to mobilize in their own struggles, alongside them; for the EZLN this meant to risk everything for something more. This is one of the most beautiful things about Zapatismo. It refuses to be still, to become a rule or a doctrine or a dogma, a subject to identify or an identity to make subject. They refuse to let power accumulate, or find too sure of a rhythm in its path. They keep changing the path, walking a new direction, trying a new talk, teaching us a new word, a new concept of struggle, of the global, of the common.

world to mobilize in their defense, to hold onto what they had, they wanted the world to mobilize in their own struggles, alongside them; for the EZLN this meant to risk everything for something more. This is one of the most beautiful things about Zapatismo. It refuses to be still, to become a rule or a doctrine or a dogma, a subject to identify or an identity to make subject. They refuse to let power accumulate, or find too sure of a rhythm in its path. They keep changing the path, walking a new direction, trying a new talk, teaching us a new word, a new concept of struggle, of the global, of the common.What the Zapatistas proposed in the Sixth Declaration depends on (at least) four points: our struggle wants to be bigger; what we want can’t be won alone; you can’t help us by lending your support, you must fight with us but you must fight your own struggle; and, the mode and form of this struggle doesn’t yet exist, it must be created.

What comes into question here is “civil society,” the name the EZLN has always used to refer the national and international public, sympathetic with the Zapatista struggle but unarmed and unwilling to take up arms. It was this civil society that took to the streets after the 1994 uprising, demanding the fighting stop so that the EZLN would not be wiped out by the much more militarily powerful Mexican army. In the 1996 dialogues of San Andres Larrainzar, again, the EZLN has recalled, we agreed to meet and negotiate with the government, at the request of civil society. But more importantly than meeting the government, we met you, national and international civil society. The San Andres Accords, in fact, the EZ states, were made among many people, they couldn’t have been made alone, just between us and the government.What Zapatismo became, from the moment when the EZLN listened to the word of the world and called a ceasefire just two weeks after the January 1994 uprising, was a global production.

Over the last decade of struggle, Subcomandante Marcos has said on behalf of the EZLN and the CCRI (Revolutionary Indigenous Clandestine Committee, the body that directs the EZLN on behalf of the base communities),

several times and to the deaf ear of many, “autonomy is not just for the indigenous.” This is an important point in light of all the eyebrows raised and foreheads wrinkled with regard to the the EZLN’s harsh criticism of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (supposedly leftist PRD candidate for the presidency). It could have been a strategic move, the wrinkled foreheads have fretted, a strategic alliance or lending of support in order to open more space for the struggle. There are clear and obvious reasons for the EZLN criticism—rejection of the electoral system of representation in general, and the insistence that they couldn’t support a party that had treated them as the PRD had and maintain even a minimum of dignity. But the Sixth makes clear another reason. It may be true that AMLO would have granted the indigenous communities of Chiapas certain rights, certain “autonomy” (though not likely the autonomy they demanded, as this would contradict neoliberal reforms that the PRD supports). But those rights would stay in Chiapas, contained in “indigenous territory.” Perhaps adequate support and protection would be legislated out from the centers of power into these small, “autonomous” communities that, while inspirational, would maintain their distance and marginality from the world, whether that be an oppressive, privileged, or merely isolated margin. But the Zapatistas will not be that margin, that contained and controlled space, that particular.

several times and to the deaf ear of many, “autonomy is not just for the indigenous.” This is an important point in light of all the eyebrows raised and foreheads wrinkled with regard to the the EZLN’s harsh criticism of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (supposedly leftist PRD candidate for the presidency). It could have been a strategic move, the wrinkled foreheads have fretted, a strategic alliance or lending of support in order to open more space for the struggle. There are clear and obvious reasons for the EZLN criticism—rejection of the electoral system of representation in general, and the insistence that they couldn’t support a party that had treated them as the PRD had and maintain even a minimum of dignity. But the Sixth makes clear another reason. It may be true that AMLO would have granted the indigenous communities of Chiapas certain rights, certain “autonomy” (though not likely the autonomy they demanded, as this would contradict neoliberal reforms that the PRD supports). But those rights would stay in Chiapas, contained in “indigenous territory.” Perhaps adequate support and protection would be legislated out from the centers of power into these small, “autonomous” communities that, while inspirational, would maintain their distance and marginality from the world, whether that be an oppressive, privileged, or merely isolated margin. But the Zapatistas will not be that margin, that contained and controlled space, that particular. In the 1996 Dialogues of San Andres, in the 1996 Intergalactic Encounter, in the 1997 March of the 1,111, in the 1999 National Referendum (the Consulta) in the 2001 March of the Color of the Earth, in the Cathedral Plaza in San Cristobal on January 1, 2003, at the biggest and most militant mobilization of Zapatistas base communities ever when Comandante Tacho hinted that something else was coming, “falta lo que falta….”: in all these moments, the EZ heard the echo, that “the struggle wanted to be bigger.” In an EZLN communiqué to national and international civil society June 21, 2005, shortly before the Sixth Declaration came out,

“…imagine what we felt when we saw and heard of the injustices and the rage of the peasants, workers, students, teachers, employees, homosexuals, young people, women, elderly, children. Imagine what we felt in our heart. We touched a heart, a rage, and indignation that we recognized because it was and is ours. But in this moment we touched it in the other. And we understood that the “we” that animated “us” wanted to be bigger, more collective….”

“…imagine what we felt when we saw and heard of the injustices and the rage of the peasants, workers, students, teachers, employees, homosexuals, young people, women, elderly, children. Imagine what we felt in our heart. We touched a heart, a rage, and indignation that we recognized because it was and is ours. But in this moment we touched it in the other. And we understood that the “we” that animated “us” wanted to be bigger, more collective….”In the Sixth Declaration, the EZLN said it louder still: this struggle is not just for the indigenous, “You’ll remember, six months ago we starting talking about ‘what’s missing’ the communiqué continues, “…well, the time has arrived to decide if we’re going to go and find what is missing. No, not find, build. Yes, build something else.”

Here in the Other Campaign, Marcos says it again, “Our struggle is not indigenist, it’s universal” (Tzinacapan, Puebla 2/13/06),

With the Sixth Declaration of the Lacondon Jungle the EZLN broke through not only the military and security issues that kept them in the mountains and jungle of the Mexican Southeast, but through the political thought of a national and international “civil society.” While many struggles across the globe have understood Zapatismo as something infinitely innovative and transformable, many others could only understand Zapatistmo as something located in Chiapas, among the indigenous, where the political role of “outsiders,” national or international, was to donate time, send money, and write denunciations and press releases condemning army and government abuses. This work was important, it allowed the autonomous municipalities to greatly expand their autonomour structures and improve their quality of life in Zapatista communities, but this was not the full capacity or scope of Zapatismo.

In the heavy, silent days after the Red Alert in June 2005, many local Chiapan and international NGOs and Zapatista solidarity groups around the world whispered about a possible military offensive, possible paramilitary prowlings, black market AK-47s and armed hummers, the incredible asymmetry of forces, The guardians of human rights—other people's human rights—bustled around, checking the old positions, reviving the old conversations, adrenaline high with the possibility of armed warfare, the discourse charged with the moral highground of righteous, humble, poor indigenous communities. Even after the EZLN clarifiee that it was neither predicting nor planning a military offensive, that it had no intent to engage militarily, that the Zapatistas would not be returning to war, the hypotheses rebounded back to troop movements, paramilitary rustlings, drug conspiracies and government set-ups. The theories of what could have spurred this reaction—the red alert and the EZLN reorganization—abounded. Except, perhaps, some hinted, this is not a reaction. Perhaps it is unprovoked, formed not out of opposition or in reaction, but in a generative movement toward something else, not something resisted but something desired.

In the communiqués following the Sixth Declaration, the EZ states clearly to civil society,

here you have a choice, you can participate directly, or you can distance yourself from what we do next. You can remain in the aura of that political moment, or you can do politics, which always refers to the present. You can stick to supporting the indigenous fight, thank you sincerely for your help, or you can join us and fight for yourselves.

here you have a choice, you can participate directly, or you can distance yourself from what we do next. You can remain in the aura of that political moment, or you can do politics, which always refers to the present. You can stick to supporting the indigenous fight, thank you sincerely for your help, or you can join us and fight for yourselves. The Zapatistas have always refused to be what any one wants or expects them to be, to be the object of anyone else’s struggle, to be anyone’s excuse not to politicize their own lives and homes. Zapatismo refuses to be anyone’s vanguard, anyone’s god; it refuses the pedestal so often provided it, the stasis of pyramids, the immobility of being on the top of a ladder so that the only direction to move is down, toppling over. It demands more movement, more freedom, the continuing flow of desire and decision that doesn't stagnate, rest on an object, pool in a position of power, concentrate in an ego. It insists on being a struggle and a strategy, a movement, literally, that generates, multiplies, mutates, expands, and networks, always in the rhythm of what is collective. It is struggle in the most profound sense—the desire to transform and be transformed, to create something different instead of hold onto what is the same.

This is the test for global “civil society,” a test not of their support, but of their desire: Do you want to be free? Can you self-determine? Can you create a common, direct a collective desire, produce something together, live more intensely? Can you exercise power or can you only ask for it? Can you produce power or can you only resist it? Can you create or can you only react? Can you be autonomous, anonymous, anomalous, or can you only be affinity, aid, accompaniment? Do you believe in autonomy or do you believe in exceptionalism? Do you believe that, behind the masks, we are you, or do you believe that, behind your masks, there is nothing?

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home